Today, I stumbled upon a website called New Literary Magazine, which posts "literary remixes." From what I can tell, the site's been inactive for a few years. But one quote, from Australian lawyers writing a report on mashups and copyright law, caught my attention:

"We now inhabit a 'remix culture,' a culture which is dominated by amateur creators - creators who are no longer willing to be passive recipients of content."

Now, more than ever, it's not just the distinguished poets and trained composers who make culture. It's the ordinary people who post videos to youtube, who decide which ones are worth watching, who create spoofs and share opinions and basically shape culture as we know it. We're all active participants--not just consumers, but creators. Youtube is teeming with mash-ups and music covers, spoofs and satires, opinion blogs, short films, fan videos and music videos. You don't need any special training or financial power--just a computer with iMovie.

And remix cultural isn't small or marginal. It's powerful, and it's center stage. Justin Bieber was discovered on youtube; Sean Kingston, Colbie Caillat, and Kate Voegele rose to fame through myspace. In Egypt, the fire of revolution started on Facebook and kept burning on Twitter. A Very Potter Musical, a Harry Potter spoof performed by Basement Arts in Ann Arbor, shot to unexpected fame through Youtube; "Scene 1" of the musical is climbing steadily toward 5 million views. And the latest viral video is always on people's lips (and sometimes even on the news).

Remix culture doesn't just allow us to create our own content; it also brings us together in a virtual community. One of the most creative uses of Youtube I've seen is the Youtube Symphony Orchestra, described on the official youtube channel as a "global endeavor devoted to sharing the love of music and celebrating humanity's vast creative diversity." Musicians auditioned on Youtube, and the talented, diverse winners (including a cello major from U of M) were invited to fly out to Sydney and perform with musicians from all over the world.

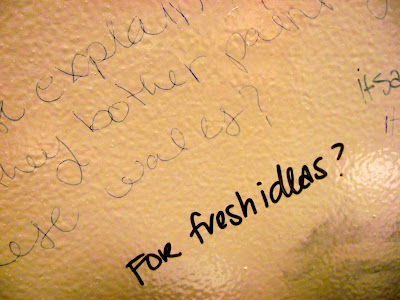

However, the internet does have its fair share of trash. Everyone's voice can be heard, and we choose who to listen to. As we've mentioned in class, freedom of speech doesn't always mean "share your opinion." We will always have that right--but we should also have the discernment to know when not to exercise it. As much as the internet is associated with worldwide connection and vast possibilities, it's also associated with cyber-bullying, offensive content, endless debates that last for pages and pages. There's no filter--we have to be careful.